In Margaret Cavendish’s tragi-comedy Bell in Campo (1662), Lady Jantil designs a tomb complex that is to be surrounded by a large grove. Jantil explains the meanings of the textiles in the three rooms that will make up her personal quarters and then goes on to say,

“Thus will I live a signification, not as a real substance but as a shaddow made betwixt life and death.” (Scene 21)

To what degree and in what manner, we might ask, did tombs and groves involve signification for people like Margaret Cavendish and John Evelyn? Lady Jantil, of course, is a character in a play, and her desire to live “as a signification” can be understood in several ways. Most obviously, the effigy that she creates of her husband, Seigneur Valoroso, points to his life as a valiant soldier. But in this sort of signification she is still corporeal herself in the capacity of an architectural designer. Her sense of her lack of substance, however, may simply be an adumbration of her impending death. As time goes on, she becomes less a creature of this world and ever more insubstantial. Eventually she disappears from life altogether. Valoroso’s effigy, by the way, is like that in the illustration to the right — a recumbent man in armor.

Men often were represented together with their wives atop tombs (see illustration below and to the left), and Lady Jantil may be suggesting, less obviously, that she will be a living effigy to accompany her husband’s which is carved in marble. That is, she will function less as a person of flesh and blood (“substance”) and more as a sign of one aspect of his life, his marriage to a worthy woman. In a third application of the word “signification,” one might say that Lady Jantil uses the decoration of her living quarters to point to her own life as a chaste and pious woman. The three rooms of her personal quarters will remind us of her scrupulous morality and of her piety. The hangings, she says, have meaning — white cloth for chastity, textiles with colors “intermixt” to signify contempt for the “varieties” of the world, and black material for her acceptance of death as the outcome of all human life.

Aristocratic families of Cavendish’s time, however, did not bury their dead in tomb complexes. They buried them in churches. Further, I believe that Margaret Cavendish, unlike her character Lady Jantil, intends the grove burial of Seigneur Valoroso to carry a mostly associative meaning rather than signification.

In his diary entry for 29 January 1645, John Evelyn, a friend of Cavendish, describes a visit to what he takes to be the tomb of the Roman orator Cicero. Located on a mountainside near Gaeta in Italy, the path to the tomb is

“Beset with myrtles, lentiscuses, bays, pomegranates, and whole groves of orange trees, and most delicious shrubs.”

The tomb itself is situated in a grove of myrtles and the experience is hugely pleasurable.

“I shall never forget how exceedingly I was delighted with the sweetness of this passage, the sepulchre mixed among all sorts of verdure; besides being now come within sight of the noble city, Cajeta [Gaeta].”

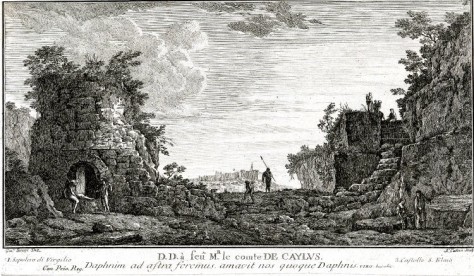

Cavendish might have learned about Cicero’s tomb during conversations with Evelyn, but, if not, it is likely that she was familiar with the locale from talking with other travellers. Clearly Cicero’s burial place was a stop on the grand tour in 1820 (see illustration to the right) and probably long before. Travellers from England, as evidenced by Evelyn’s diary, also were taken to tombs purported to be of the Roman dramatist Plautus and a number of less-well-known figures including Valerius Volusi, tombs located in leafy environs.

The grove surrounding Jantil’s tomb complex is described thus:

“Lawrel, Mirtle, Cipress, and Olive . . . . this Tomb placed in the midst of a piece of ground of some ten or twenty Acres, which I would have incompassed about with a Wall of Brick of a reasonable height.”

While Jantil’s signification for her three rooms points clearly and directly to moral and pious meanings, Cavendish’s associative approach makes a fuzzy and indirect connection between the memory of Seigneur Valoroso and a classical world of tombs located amidst groves of Mediterranean trees.

In her collection of stories in verse and prose, Nature’s Pictures (1656), Cavendish tells the tale of two lovers who die tragically. The lady, who ends her life with a pistol shot to the heart, utters the following request.

Let no friends marble toms erect upon

Our graves, but set young myrtle trees thereon.

Those may in time a shady grove become,

Fit for sad lovers Walks, whose thoughts are dumb. (Nature’s Pictures, p. 45)

The lady also asks for her cheeks and those of her lover to be anointed with poplar sap and for each of the dead to be crowned with a cypress garland. Rather than a marble monument, she foresees an imaginary classical temple to Love that “may walk in moving-Brains.”

If Jantil says that she will exist outside of substance, Cavendish’s lady from Nature’s Pictures thinks that memory is a process dependent on the cerebral activity of living people — in this case the “sad lovers” who will walk in the grove. The quote in full:

Thus, though w’are dead, our Memory remains;

And, like a Ghost, may walk in moving-Brains;

And in each Head Love’s Altars for us build,

To sacrifice some Sighs, or Tears distill’d.

By writing about “moving-Brains,” Cavendish aligns herself with one sort of contemporary natural philosophy which maintained that all thought is contained in matter in motion. Her philosophy of mind has much in common with that of Thomas Hobbes, with whom she was acquainted through the Cavendish Circle.

Becoming quite specific, the lady from Nature’s Pictures foresees an imaginary temple to the god Eros. This temple will be created for use with its own kinds of sacrifices and ablutions. The imaginary temple, I expect, corresponds in a loose way to the actual temple of Venus that John Evelyn designed in the 1650s for the garden of his birthplace at Wotton House in Surrey. (The temple, now on the grounds of a hotel, is pictured at the top of this page.)

There can be no doubt that Evelyn was a very serious Christian, but, to my knowledge, he did not make clear and direct claims for moral or pious signification for the temple at Wotton House. Rather, like Cavendish, he hoped to create associative meaning. His temple and the surrounding garden evoke a generalized heritage claimed from Greece and Rome.

It may be that what I have called “fuzzy” associative meaning and have connected to Evelyn’s temple was well suited to the English nobility, which included a mix of Roman Catholics and members of the Church of England. (Evelyn probably would not have worried much about pleasing Puritans, though his temple would have been inoffensive where most of them were concerned.) The religious architecture of classical Greece and Rome, I think, was able to provde a broadly inclusive and richly irenic heritage of civility and domestic good order in the aftermath of brutal and chaotic civil wars.

One feature of Lady Jantil’s grove remains to be explained or at least given some attention, the wall of “reasonable hight.” Jean de La Quintinie’s Compleat Gard’ner in John Evelyn’s translation of 1693 suggests that kitchen gardens have walls that are “pretty high” (vol 1, part 2, chapter 1). Such gardens have doors with locks and the walls are designed to discourage pilfering. Cavendish wants to make sure that Jantil’s wall is not understood to be of this sort.

Margaret Cavendish probably has in mind a wall intended to keep farm animals from straying into where they would be a nuisance, a structure perhaps waist high (see illustration above and to the right). Lady Jantil’s grove, then, is partly reminiscent of the English countryside, while the grove of the lady from Nature’s Pictures, which has no wall at all, is more thoroughly in the classical tradition — or at least that tradition as it was known to English travellers. Cavendish, as a long-time resident of Antwerp, would have encountered a steady stream of English people going to and coming back from Italy. Antwerp was definitely on the beaten path for the English venturing abroad.

My sense is that Margaret Cavendish does not entirely sympathize with Jantil as a character for several reasons. Most importantly, the tomb complex is too grandiose — especially when compared with the understated power of the lovers’ burial in Nature’s Pictures. The tomb complex also is cluttered, i.e., overly full of statuary and of paintings of Seigneur Valoroso. That said, Jantil is largely a sympathetic figure as a loyal widow. We modern readers probably do not mind Jantil’s small failings, because they allow her to become a believable human being.

A few final observations. 1) Evelyn labels his temple on the plan for his garden, “grotto.” Since the structure is built into the side of a hill, it is in that regard something of a cave, as grottos tend to be. The temple also makes use of water works. Be these features as they may, the building is otherwise instantly recognizable as a temple in its form. It is a temple with the features of a grotto rather than the other way around. 2) Cicero’s tomb, in the print, appears to include a high wall, though one that is thoroughly overgrown with vegetation. 3) Cavendish herself revelled in the variety of the world. One of her books carries the title The World’s Olio, which suggests a savory stew of mixed ingredients.